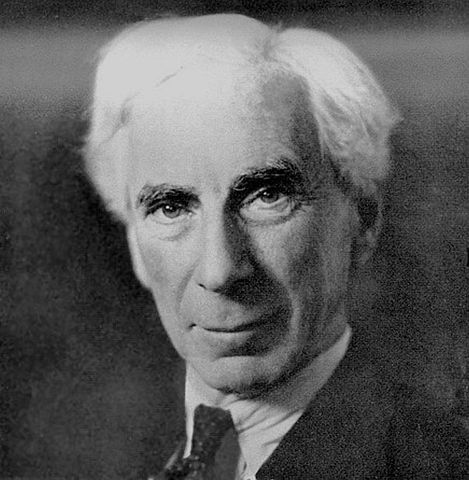

Bertrand Russell – How to Find Value in Philosophy

Philosophy had often been ridiculed by academics (inside and outside of the field) and non-academics for being lofty and complicated, and even futile and useless.

Stephen Hawking has even proclaimed that ‘philosophy is dead’. In The Grand Design (2011) he says that philosophy,

Has not kept up with modern developments in science, particularly physics. Scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge.

To those who see the study and contemplation of philosophy as vital to understanding life itself, these critical opinions can be difficult to swallow.

Many defenders of philosophy have suggested that Hawking must not understand what philosophy truly is – how it is defined, or the value it brings. That, or he is using a very different definition of philosophy.

Looking back nearly 100 years before Hawking’s proclamation of the death of philosophy, we can see how one famous philosopher and logician explained and defined the importance of philosophy.

In Bertrand Russell’s seminal book, The Problems of Philosophy (1912), he outlines the value of philosophy in the final chapter of the book called, ‘The Value of Philosophy’.

Russell acknowledges that,

Many men, under the influence of science…, are inclined to doubt whether philosophy is anything better than innocent but useless trifling, hair-splitting distinctions, and controversies on matters concerning which knowledge is impossible.

Russell says, however, that in order to understand the value of philosophy, ‘we must free our minds from the prejudices’ of what he calls the ‘practical man’. The ‘practical man’ is someone who,

Recognizes only material needs, who realized that men must have food for the body, but is oblivious of the necessity of providing food for the mind…It is exclusively among the goods of the mind that the value of philosophy is to be found; and only those who are not indifferent to these goods can be persuaded that the study of philosophy is not a waste of time.

We might think of a practical person as one who simply gets through their uninspiring workday only to come home and turn on a mind-numbing television program until it is time for bed. This is not to say that there is anything wrong with some mind-numbing once in a while, but for many people, this is their existence.

What about the argument that philosophy does nothing to advance science or knowledge in general?

This belief stems from a misunderstanding of what philosophy is – by definition. Defining philosophy, however, is often easier said than done. Not everyone agrees on one simple definition.

If we look at the origin of the word, it tells us that philo is Greek for ‘love’ and sophia is Greek for ‘wisdom’ or ‘knowledge’. So philosophy is the love of knowledge or wisdom.

Philosophers seek knowledge – they try to uncover what is unknown. Once the unknown becomes known, however, it is no longer a part of philosophy.

More from Russell,

As soon as definite knowledge concerning any subject becomes possible, this subject ceases to be called philosophy, and becomes a separate science. The whole study of the heavens, which now belongs to astronomy, was once included in philosophy; Newton’s great work was called ‘the mathematical principles of natural philosophy’. Similarly, the study of the human mind, which was a part of philosophy, has now been separated from philosophy and has become the science of psychology. Thus, to a great extent, the uncertainty of philosophy is more apparent than real: those questions which are already capable of definite answers are placed in the sciences, while those only to which, at present, no definite answer can be given, remain to form the residue which is called philosophy.

So by definition, philosophy cannot have knowledge. It does, however, find knowledge and gives birth to the sciences.

It may be argued, however, that philosophy has not brought much to the plate in the last few hundred years. Does that mean we should cease seeking knowledge?

Many of the questions we have may seem impossible to answer. Russell says,

Yet, however slight may be the hope of discovering an answer, it is part of the business of philosophy to continue the consideration of such questions, to make us aware of their importance, to examine all the approaches to them, and to keep alive that speculative interest in the universe which is apt to be killed by confining ourselves to definitely ascertainable knowledge.

We cannot stop asking questions. It is clear that we do not have all of the answers. The questions we have may seem impossible to answer, but if someone from 500 years ago could see our lives today they would think it impossible.

Russell says we must open our minds to the world of this unknown.

The value of philosophy is, in fact, to be sought largely in its very uncertainty. The man who has no tincture of philosophy goes through life imprisoned in the prejudices derived from common sense, from the habitual beliefs of his age or his nation, and from convictions which have grown up in his mind without the co-operation or consent of his deliberate reason. To such a man the world tends to become definite, finite, obvious; common objects rouse no questions, and unfamiliar possibilities are contemptuously rejected. As soon as we begin to philosophize, on the contrary, we find… that even the most everyday things lead to problems to which only very incomplete answers can be given. Philosophy, though unable to tell us with certainty what is the true answer to the doubts which it raises, is able to suggest many possibilities which enlarge our thoughts and free them from the tyranny of custom. Thus, while diminishing our feeling of certainty as to what things are, it greatly increases our knowledge as to what they may be; it removes the somewhat arrogant dogmatism of those who have never travelled into the region of liberating doubt, and it keeps alive our sense of wonder by showing familiar things in an unfamiliar aspect.

There are many people who prefer to live their life ‘definite, finite, obvious’ and that is fine. Fortunately, however, there are many who will not accept a non-contemplative life.

Thus contemplation enlarges not only the objects of our thoughts, but also the objects of our actions and our affections: it makes us citizens of the universe… In this citizenship of the universe consists man’s true freedom…

Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions, since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather for the sake of the questions themselves; because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible, enrich our intellectual imagination and diminish the dogmatic assurance which closes the mind against speculation; but above all because, through the greatness of the universe which philosophy contemplates, the mind also is rendered great, and becomes capable of that union with the universe which constitutes its highest good.

Philosophical contemplation enriches our lives and opens our world as we explore the world in new ways. As we see here with Russell and many great philosophers before him (Socrates and Aristotle, for example), philosophy should be seen as an expression of the highest good. As Socrates says, ‘An unexamined life is not worth living’.

Russell continues,

Apart from its utility in showing unsuspected possibilities, philosophy has a value, perhaps its chief value, through the greatness of the objects which it contemplates, and the freedom from narrow and personal aims resulting from this contemplation. The life of the instinctive man is shut up within the circle of his private interests: family and friends may be included, but the outer world is not regarded except as it may help or hinder what comes within the circle of instinctive wishes. In such a life there is something feverish and confined, in comparison with which the philosophic life is calm and free. The private world of instinctive interests is a small one, set in the midst of a great and powerful world which must, sooner or later, lay our private world in ruins. Unless we can so enlarge our interests as to include the whole outer world, we remain like a garrison in a beleaguered fortress, knowing that the enemy prevents escape and that ultimate surrender is inevitable. In such a life there is no peace, but a constant strife between the insistence of desire and the powerlessness of will. In one way or another, if our life is to be great and free, we must escape this prison and this strife.

Eliminating philosophy from our lives would be like eliminating learning itself. Read more on the value of Philosophy.

Leave a Reply